In part one of this series, I outlined five principles for building a high performing team. Agreeing on these is the easy part. Becoming a team, and functioning well as a team day in and day out, is hard work. This post outlines some “how to” tips to put these principles into practice!

But first a note to you, the leader: You model the way, deciding when to direct, when to coach, and when to step back and let others lead without you. Ideally, if your team is thriving, times to direct are minimized, and times to coach or simply stand back are maximized. But you are responsible for insisting on the conditions to make this happen. So let’s assume the one place where you will surely be authoritative is in explaining and then ensuring fidelity to the principles. From there, there are a range of ways in which you can participate, coach, and simply stand back as the team learns, collaborates, and “plays” to win!

Principle 1: Collective performance must trump individual performance in order to make progress.

As a leader, you want to establish this idea off the bat. But you’ll need feedback and suggestions from team members about what this looks like in action. Lots of dialogue in the early days of teaming can go a long way. Work with your team to explore why you can accomplish more if you function as a team - and how that differs from being merely a group of leaders. Once you've established why collective performance matters most, you can identify the conditions needed to ensure this can happen. It might start with questions like:

How do we want to feel as a team?

What do we need to know as a team?

What do we want to be able to do together?

How will we assess and measure our progress?

What do you need from me, your leader, to make this happen? (this is an important question and encouraging your team to offer you honest feedback - and receiving it with gratitude - is essential)

As you explore these questions, you’ll likely name the behaviors, practices, and mindsets that either encourage or inhibit collaboration towards collective performance.

The next step is to establish norms. Norms are agreements about how you will work together as a team, and they name the mindsets and behaviors that drive teaming. Norms we’ve heard teams create include “assume positive intent”, “share the air”, and “hard on content, soft on people.” Your team will craft its own -- and team members will be creative and thoughtful.

Once you can agree on norms, you’ll also want to talk about methods to course correct when someone steps out of the norms – make it fun, non-punitive and easy to implement. Many teams have a code word or signal when someone strays – and use it with joy!

Creating a shared commitment to collective performance and then establishing the conditions for success is step one.

Principle 2: Teams thrive when each member has a valued role with clear, shared purpose.

A team charter is a useful tool for making your team’s purpose explicit – and mapping individual roles against the goals you pursue together. You’ve established conditions and ground rules but now you need to determine what you are trying to accomplish and how each of you will contribute to the overarching goals. We encourage teams to draft a charter that includes a statement of mission, a delineation of roles and responsibilities, and priority goals or areas of focus. The charter should recognize and address every member of the team – speaking to them through the lens of their collective performance.

Once the team has established its charter, each team member has a clear sense of what matters most – and how their role as an enterprise wide leader is paramount. But they still have functional domains, and the crafting of a charter models an exercise they can do with their own teams – this is how leaders knit together the work up, down, and across the organization.

We have a helpful toolkit for building a team charter. Let us know if you’d like to use it!

Principle 3: Trust is the foundation, but you can’t win the game without shared understanding of strategy.

Trust is a core condition for success -- one that must be built and nurtured over time -- so attend to practices that build confidence both in you as the leader and among the team. Trust doesn’t develop through ropes courses, clever team building games, and fun social events. Sure, these things can help, but the real work is in building confidence through consistent experience, and working together to understand and pursue the strategic aims of the organization.

As a leader, first explore with your team what practices (for meetings, communications, collaboration, etc.) help build confidence in your ability to achieve your goals. Remember, you’ve identified behaviors that hinder or encourage great teaming – so design your practices to meet those needs and ensure all team members feel valued and clear with respect to their roles.

Teams are not afraid to experiment with new practices – so talk about how they work. Are they advancing you towards your goals? Are they modeling collaboration and shared purpose? Recalibrate often, and as a leader, know when you need to work with a particular team member who may not be fulfilling their potential.

What are practices? Think meetings, agendas, schedules, project management systems, and organizational structures like committees designed to make work happen. These practices are not meant to be static – but they often slowly cement themselves into organizational life. Model the way for agility in your organization by trying new ways of working to stimulate progress.

Often, as teams explore what’s in the way, they find an audit or assessment of systems and practices can help to redesign ways of working that support talent!

Principle 4: Players need to train, and teams need to practice.

Practices are supporting structures. But practicing as a team is where the learning and development happens. As the “leader as coach” your job is to create space for the team to 1) practice without you on the field and 2) reflect on their performance. As a coach, you’ll do this with them as a collective and as individuals. So, take out your charter, look at your goals, and ask them to talk about it.

How were we going to get there?

What’s our strategy to make this happen?

How did we do?

What needs to change?

What do you need from each other? From me?

Real time feedback and a next cycle of practice develops the team.

Each team member also needs attention, and has particular strengths to leverage and weaknesses to manage. As a coach, how can you help that performer grow – and support them with targeted skill building? How can peer coaching and collaboration target skills and leverage strengths?

As a leader/coach, nurture your players’ success by ensuring each individual not only understands their role in advancing the work of the team, but also by aligning their personal goals, feedback and assessment to maximize their contribution to the team’s performance.

We help teams and the team members from the get-go to develop and utilize coaching skills - we think it's the single best skill every leader has to unleash potential within themselves and with their colleagues and direct reports. Build a coaching culture and your practice will be a lot more effective.

Principle 5: High functioning teams model the way and shape culture.

When you draft your team charter, don’t forget that this principle is at the core of your mission. Your overarching job is not to accomplish the goals, it's to build and cultivate an organization of talented people who together can do the job. That’s why coaching skills are so important to develop in your leaders.

As a regular part of reflection with the team and with your team members ask:

How are you developing your peers and your people?

How are you modeling for them the work we do as collaborators?

What practices are you spreading and scaling in your functional work to help build the culture we need in our organization?

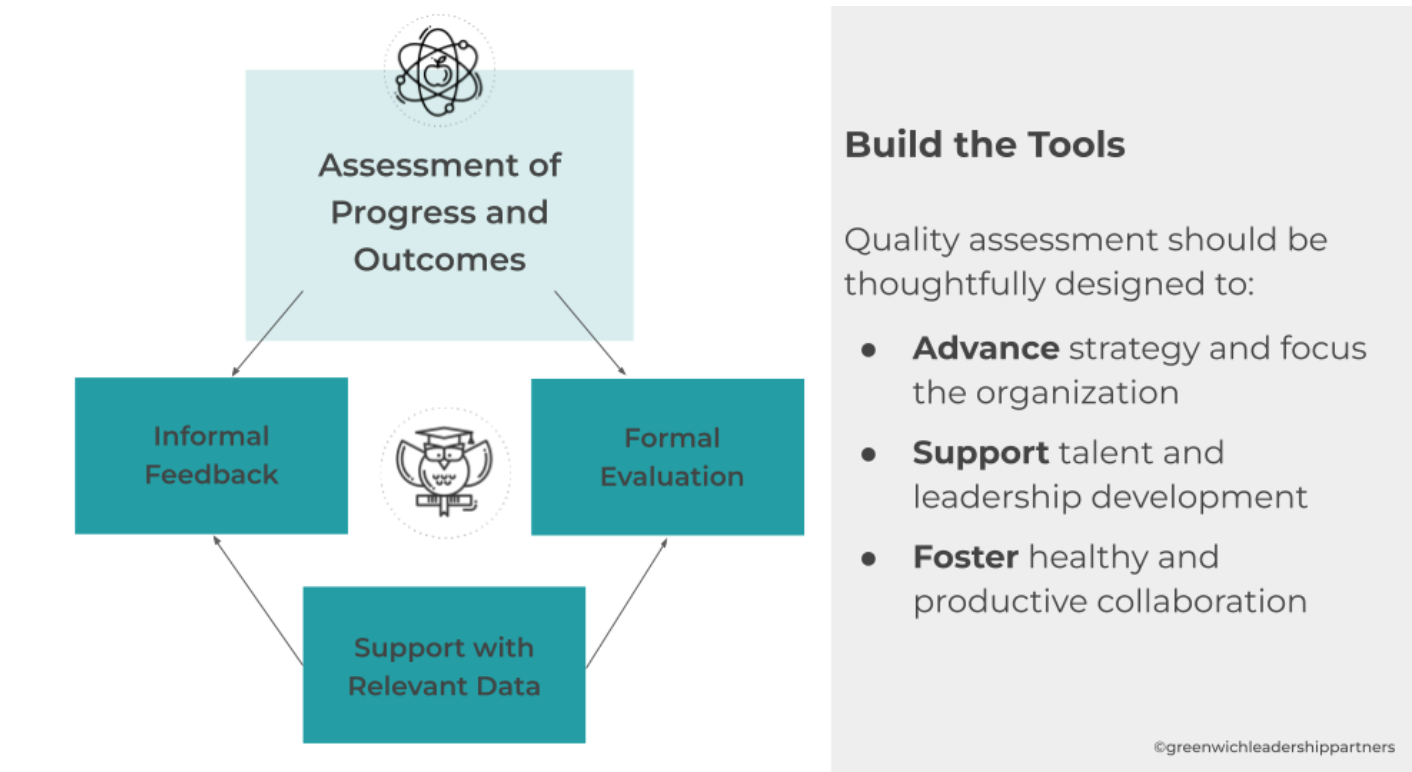

Finally, assess yourselves both as a team and against this critical element of purpose. If you don’t measure it, you’ll lose sight of it. Systems for assessment and evaluation need evidence based approaches to help you make progress. And don’t assess once a year. Make this a regular part of your work - with informal check-ins and formal efforts to solicit feedback - from your team and from other members of the organization. Return to the questions we offer at the top of this blog as an entry point for predictive reflection.

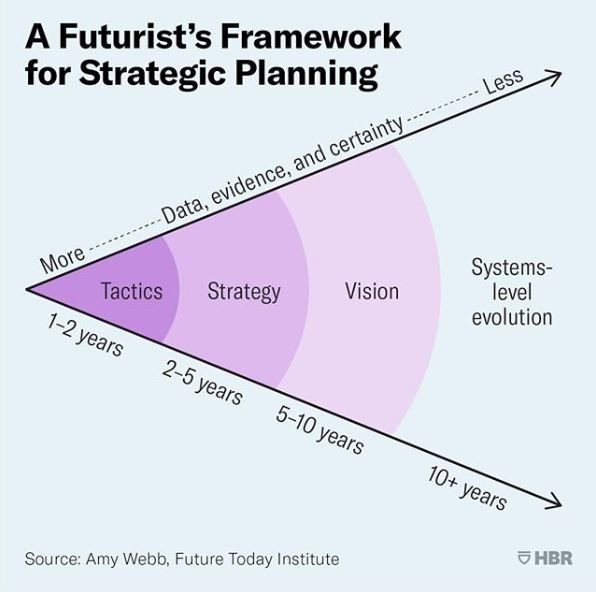

A word on formal assessment: Measurement is hard – and establishing leading and lagging indicators for performance can be confusing. But a leadership team that doesn't hold itself accountable to how it develops talent across the organization is a team that is working at a fraction of its potential.

In Part three of this series we will dive deeper into assessment of team and team member performance -- how to measure, and what to do when you just don’t have the talent you need on your leadership team!